The Holy see has released a public statement “Repudiating” the concepts of colonization, including the doctrine of Discovery.

The statement from the Church’s magisterium is somewhat vague and could be interpreted in multiple ways. To thoroughly understand the implications of such a statement and ensure that a doctrine is legally and effectively revoked, several key steps must be undertaken.

Denotative

- Repudiate: To reject the validity or authority of something.

- Denotative meanings:

- Reject as invalid or untrue.

- Refuse to acknowledge or pay (a debt, for example).

- Disown or refuse to be associated with.

- Denotative meanings:

- Ripudiare (itallian)

- Denotative meaning:

- The same as above

- Denotative meaning:

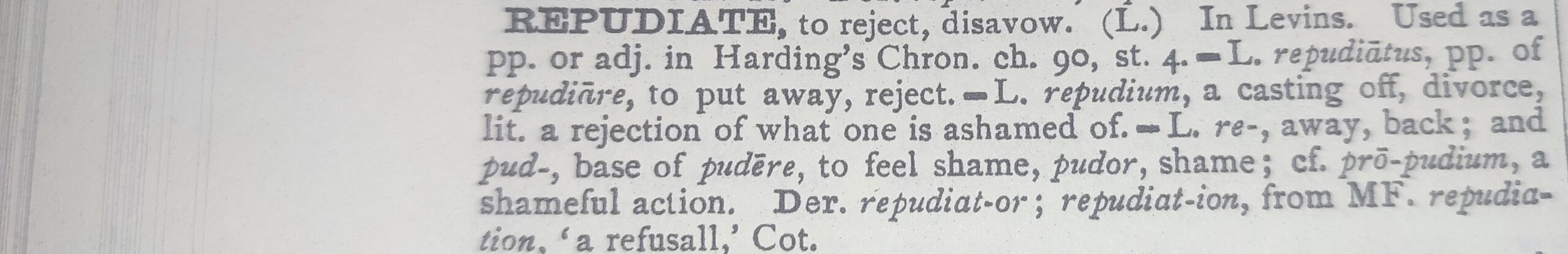

Etymological

- Repudiate: (Latin) repudiatus [to put away, reject, a rejection of what one is ashamed of]

- Etymological Meaning:

- re- prefix- again

- pudiate (Latin) Pudere of pudet – [to feel ashamed]

Examining the statement of line 7. “In no uncertain terms, the Church’s magisterium upholds the respect due to every human being. The Catholic Church therefore repudiates those concepts that fail to recognize the inherent human rights of indigenous peoples, including what has become known as the legal and political “doctrine of discovery”.”

To repudiate those concepts can be interpreted as: to put away those concepts or to reject these ideologies as refusal of acknowledgment.

Lets use the denotative definition.

…The Catholic Church therefore *refuses to acknowledge* those concepts that fail to recognize the inherent human rights of indigenous peoples….

or how about,

…The Catholic Church therefore *Disowns or refuse to be associated with* those concepts that fail to recognize the inherent human rights of indigenous peoples….

To not acknowledge a doctrine is not the same as revoking and/or making the document null and void. this is why etymology is important.

For those who feel like this is type of word analysis is splitting hairs, it is. It is also imperative to know what is being stated denotatively, not connotatively.

Steps for Revoking a Doctrine

- Formal Revocation Statement:

- A clear, unequivocal statement should be issued by the authoritative body (e.g., the Church or a government) explicitly stating that the doctrine is null and void.

- The statement should specify that the doctrine is no longer recognized, upheld, or valid.

- Legal and Institutional Actions:

- Legislation: Enact laws that formally revoke the doctrine and remove any legal basis it might have provided.

- Policy Changes: Implement policies that actively counteract the principles of the doctrine.

- Public Acknowledgment and Restitution:

- Acknowledgment: Recognize the harm and injustices caused by the doctrine.

- Restitution: Take steps to address and remedy the impacts on affected communities.

Example of a Clear Revocation Statement

A clear revocation statement might read as follows:

“The Catholic Church formally revokes the Doctrine of Discovery and declares it null and void. We recognize the inherent human rights of indigenous peoples and reject any past or present interpretations of this doctrine that deny these rights. Effective immediately, the Church disavows any legal, political, or social implications of the Doctrine of Discovery and commits to rectifying its historical and ongoing impacts.”

Legal Actions by Governments

- Legislation: Pass laws explicitly nullifying any legal precedents based on the Doctrine of Discovery.

- Court Rulings: Have high courts overturn rulings that were based on the doctrine, setting new legal precedents.

- Policy Reforms: Reform policies in land rights, sovereignty, and other areas affected by the doctrine.

Concrete Steps for the Catholic Church

- Issuance of a Papal Bull or Encyclical: A new papal bull or encyclical explicitly revoking the earlier documents that constituted the Doctrine of Discovery.

- Educational Programs: Implement educational programs within the Church to inform clergy and laity about the revocation and its implications.

- Engagement with Indigenous Communities: Work directly with indigenous communities to address historical grievances and support their rights and sovereignty.

Conclusion

While repudiation indicates a strong disapproval and rejection, legal and historical doctrines require explicit and formal actions to be effectively revoked. This involves clear statements, legal reforms, and actions that ensure the doctrine is no longer in effect in any capacity.

Additional Reading Below:

Click this link for the Vatican’s full statementEtymological reference: “An Etymology Dictionary of The English Language” by Walter W. Skeat

Use of the doctrine in the supreme court. (Wikipedia Sources):

In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the US Supreme Court found that the Cherokee Nation was a “domestic dependent nation” with no standing to take action against the state of Georgia.

In Worcester v Georgia (1832), Marshall re-interpreted the doctrine of discovery. He stated that discovery did not give the discovering nation title to land, but only “the sole right of acquiring the soil and making settlements on it.” This was a right of preemption which only applied between the colonizing powers and did not diminish the sovereignty of the indigenous inhabitants. “It regulated the right given by discovery among the European discoverers, but could not affect the rights of those already in possession, either as aboriginal occupants, or as occupants by virtue of a discovery made before the memory of man.”

In five further cases decided between 1836 and 1842, Mitchel I, Fernandez, Clark, Mitchel II, and Martin, the Supreme Court restored the rule in Johnson that discovery gave the discovering nation ultimate title to land, subject to a right of occupancy held by indigenous peoples.

In Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1979), the Supreme Court held that discovery deprived tribes of the right to prosecute non-Indians. In Duro v. Reina (1990) the court held that tribes could not prosecute Indians who were not a member of the prosecuting tribe. However in November 1990, the Indian Civil Rights Act was amended by Congress to permit inter-tribal prosecutions.

As of March 2023, the most recent time the doctrine was cited by the Supreme Court is in the 2005 case City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York, by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in the majority decision.